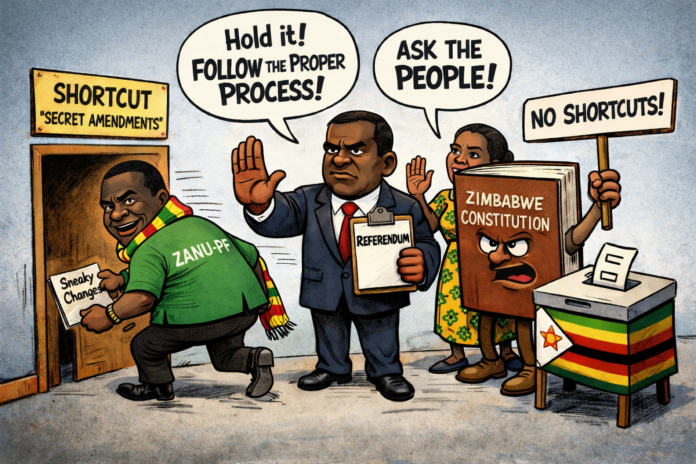

A group of war veterans has approached the Constitutional Court, accusing President Emmerson Mnangagwa of spearheading an unconstitutional power grab through the proposed Constitutional Amendment Bill (No.3).

Their argument is weighty. They cite Section 328(7), which clearly states that an incumbent cannot benefit from amendments that extend their own term. They argue that allowing Parliament to elect the President, instead of the people, undermines universal suffrage and violates the spirit of the Constitution.

The legal challenge is legitimate. Courts exist precisely to interpret constitutional boundaries.

But let us be clear about something.

The Constitution does not prohibit amendments. It regulates them.

ZANU-PF is legally entitled to table constitutional reforms. They are allowed to debate them. They are allowed to draft them. That, in itself, is not unconstitutional.

What matters is the process.

Under the 2013 Constitution, amendments affecting presidential term limits and the structure of executive authority are not ordinary changes. They are entrenched provisions. That means they require not only a two-thirds majority in Parliament, but also approval through a national referendum.

That is the safeguard.

A referendum is not a public hearing.

It is not a consultation meeting.

It is not a Cabinet approval.

It is a direct national vote.

If the proposed reforms seek to extend the President’s tenure or alter how the President is elected, then the Constitution dictates that the final decision must rest with the people of Zimbabwe.

This is where the national conversation should focus.

Litigation may delay or clarify aspects of the process. It may test the legality of the President chairing discussions on amendments that could benefit him. It may interrogate Section 328(7). But ultimately, the decisive battleground is procedural legitimacy.

If the government attempts to bypass a referendum where one is constitutionally required, that is where the real constitutional breach occurs.

If a free and fair referendum is held and Zimbabweans approve the changes, that decision carries democratic legitimacy.

But if reforms are pushed through without the required popular vote, then they are not just politically controversial — they are constitutionally defective.

The debate must therefore shift from outrage to vigilance.

This is not about whether amendments can be made.

They can.

It is about whether they will follow the constitutional path laid out in 2013.

The Constitution anticipated moments like this. That is why entrenched clauses exist. That is why Section 328(7) exists. That is why referendums exist.

Noise is not enough. Panic is not strategy.

What is required now is clarity.

If the reforms affect presidential term limits or executive structure, the people must decide.

Anything less undermines constitutional governance itself.